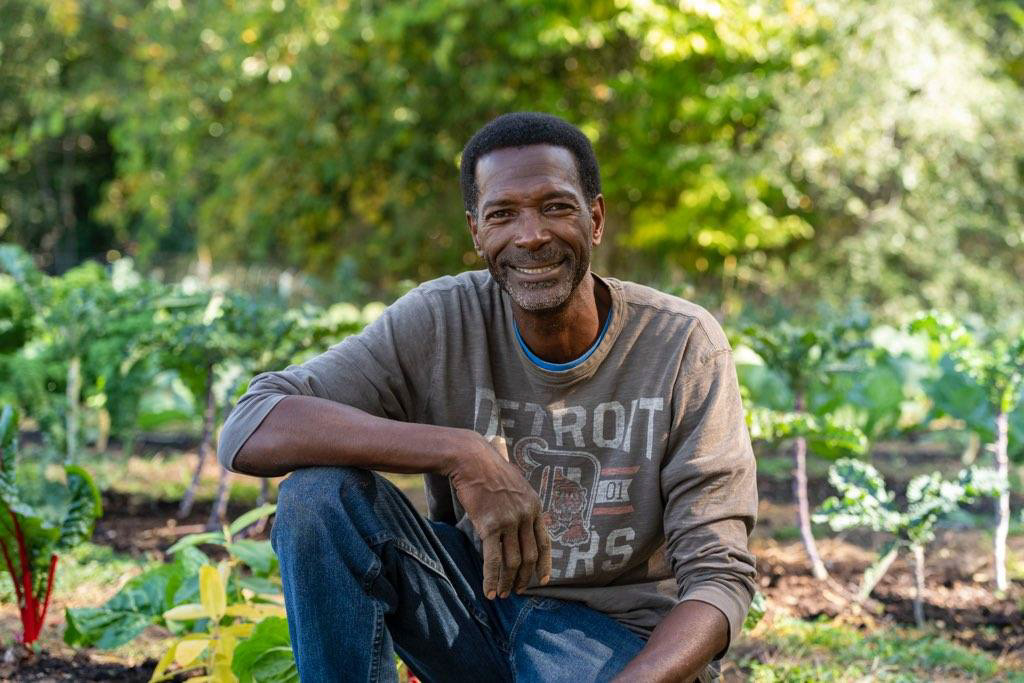

Melvin at WTPOF.

Torrence Williams | Washtenaw Voice

by XAILIA CLAUNCH

Staff Writer

Melvin Parson describes his neighborhood growing up as one that normalized going to prison, almost like a “twisted rite of passage.”

After serving three prison sentences of his own, he set out to make a change in the community for the better.

Parson is the founder of We the People Opportunity Farm in Ypsilanti, an organic farm that employs formerly incarcerated men and women in order to help them reintegrate into the community. The internship lasts for nine months, and then WTPOF helps guide the interns towards continued education or meaningful employment.

WTPOF aims to help formerly incarcerated individuals by reintegrating them into the community and “spring-boarding” them to continued education or employment.

Torrence Williams | Washtenaw Voice

Parson started WTPOF in 2015 after battling addiction and the prison system himself. He wanted to provide opportunities for people who’d gone through what he had, and he also wanted to provide representation for other Black farmers.

“At my core, I’m a champion of social justice and social equality,” Parson said. “During my trips to the Ann Arbor Farmer’s market, you know, to find out what kale or radishes were or something like that, I saw nobody that looked like me shopping there. I looked around at the farmers, and none of them looked like me either. I wanted to have a seat at a table, to bring some pepper to all of that salt that I saw.”

“I had this friend that knew me better than anyone else at the time. He would send me pictures of farmers, and all of them were white men. He knew that that would agitate me,” said Parson.

The farm started out as a single-member LLC in 2015, then known as We the People Grower’s Association. After raising money through crowdfunding, Parson was able to turn the farm into a non-profit organization in 2018, which became known as We the People Opportunity Center, and finally, We the People Opportunity Farm.

Torrence Williams | Washtenaw Voice

The need for programs to help people who were formerly incarcerated find jobs is huge in the United States. Formerly incarcerated people are unemployed at a disproportionate rate in America compared to those who haven’t served time. According to a Prison Policy study, the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is 27%, which is higher than the peak unemployment rate of the Great Depression.

Currently, the farm has two interns at a time, but Parson hopes to expand to four.

Parson also wants to ensure that his interns earn a liveable income, and is raising their hourly wage from $14 to $17.

“One of the things I’ve been thinking about lately is kindness and dignity, not only for me and how I treat people, but for my organization,” Parson said.

“Last year we paid our interns $14 an hour, which is not a lot of money. One of our interns had to leave because it just wasn’t enough for him. And I get it, I get it. Washtenaw County has what’s called a ‘fair living wage,’ and here it’s $17 per hour. So this year, we’re going to pay our interns that, to show them that we value them.”

Parson plans to help his interns be successful beyond their internship.

“Even with $17, it’s still not that much, but our goal is after they’re with us for nine months, we off-ramp them in a way that connects them with full-time employment, or maybe a school or trade program. And staying connected, even afterward, like building a family,” said Parson.

Another goal of Parson’s is to establish a fund for former interns who may need help down the line.

“We’re starting an endowment fund, for when they graduate and may run across some challenges, I mean, s— might get tight, and they may be behind on their rent or need a used car, we want to be able to help them as they try to reintegrate into a sometimes unforgivable society,” explained Parson.

Parson said that WTPOF finds its interns by building relationships with the community, such as the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office, and the Department of Corrections programs for “offender success,” along with some other agencies.

“We introduce ourselves and build those relationships with them, and if they find someone who would be a good fit for our program, they contact us,” said Parson.

Apart from focusing on its interns, WTPOF is working to find a way to distribute food to the community. The farm is located on the property of Grace Fellowship Church, which distributes food to community members in need. During the pandemic, Parson and his interns handed out fresh produce to people receiving food from the church.

“We just came alongside them, outdoors, brought a couple totes, filled them up with water, stuck our produce in there, and when cars lined up to get food from the church, we would go up to the cars and say, ‘Hey, how you doing, I’m a member of WTPOF, our farm is about 50 yards from here. We grow fresh organic food and we were wondering if you would be willing to take some off of our hands at no cost for you,’” said Parson.

“We’re still trying to figure out if it’s a program or if it’s just part of what we do to give back to the community.”

WTPOF has a partnership with Zingerman’s, whose co-founder Paul Saginaw has taken the role of interim president at the farm. The produce from the farm is used at Zingerman’s Roadhouse.

Parson expressed his gratitude for the community, interns, and volunteers at WTPOF.

“Part of who we are is that community engagement piece. We feel honored and privileged to have a space where people can come and put their hands in the soil and feel useful and helpful, and feel all those things that being out there does.”

“If someone wants to help, they can go to our website to get started,” said Parson.

Melvin’s son and grandson, Melvin Parson II and Million Lloyd Lamar Parson.

Torrence Williams | Washtenaw Voice