Vardan Sargsyan | Washtenaw Voice

Catherine Engstrom-Hadley

Staff Writer

This week, my youngest child turned nine months old, which also marks nine months of my Caesarean section scar not being closed. My story should be rare, but it isn’t. In fact, compared to others, my story is tame.

I had spent most of my first pregnancy preparing for a natural birth; I had images of birthing my child with a clear mind, holding him for his first moments with a golden glow between us. However, our birth plans changed drastically when I developed a rare condition called obstetric cholestasis, which is associated with high rates of stillbirth. We opted for a gentle C-section to decrease the risk to our child. Even though it wasn’t the magical bathtub birth I had pictured, it was still a transformative experience for me. My body felt powerful and amazing. I was in awe of the life it had made.

When we were pregnant with my second child, we hoped for a VBAC, or vaginal birth after Caesarean, but decided to plan for a C-section, too, to be prepared. We made a birth plan and selected a doctor and a hospital that said they were patient-centered and worked with birth plans.

A month before our due date, a blood pressure test came back high. We were concerned, so we went in for further tests at the hospital.

At the hospital, a doctor we had not met before came to see us. The doctor kept insisting I already had preeclampsia, but I had not. The doctor said that if I didn’t have it before, I certainly had it now and that we would have to deliver by C-section that night.

I felt scared and like we were being steamrolled into something. I felt as if my body was failing to do the one thing it was designed to do.

Once in the operating room, they attempted to administer epidurals five separate, grueling times. I struggled to get in the correct position, and the doctor became impatient and snapped at me. My nurse held my hand while I cried.

The blood pressure monitor started to drop. I felt sick. I saw nurses running and doctors frantically tossing steel implements near the table to which I was strapped.

“Get the husband!” someone yelled. I vomited all over the floor, a reaction to the medicine. I could hear the fetal Doppler drop.

My husband bursted in, his hands shaking. Was I dying? Was the baby okay? No one would answer.

After 4 minutes, I heard a cry. The sense of relief in that second was palpable; my child had made it. But his lungs were not functioning like they should. Per my birth plan, my husband was whisked away with the baby, who I had only seen for a moment over the surgical curtain.

The next time I saw my baby was an hour and a half later when he was transported to the Newborn Intensive Care Unit for recovery. He was hooked to a breathing machine and tiny IVs covered his body. All I wanted to do was hold him.

I felt small and ignored, and like I had failed my child. Why didn’t I advocate for myself more? Should I have stuck to my guns and waited to give birth?

I was given an IV treatment that made me a fall risk, so I could not visit my baby in the NICU. I was exhausted, but I could not sleep.

Finally, after 12 hours, a nurse took pity on me and wheeled me down to see my baby. I could barely hold him, both of us tangled in cords. But that 15-minute visit with him was heaven.

Finally, after 24 hours, my husband and my child could come to my room. I was elated and could sleep.

The nurse who initially took care of us came to visit and cried when she saw the baby was okay.

“I thought we were going to lose both of you, but I’m so happy you made it,” she said. That was when it hit me—we really did almost die.

The pain was much greater than my first birth and it was the lowest scar I’ve ever seen. At one point, a man came in and told me he worked in surgery, and he could answer any questions I had. When I asked for more details about what happened, he told me he wasn’t sure about my case, that he actually hadn’t looked at it and he would be back. I never saw that man again.

When we finally were released and returned home, we realized my medication prescription had been sent to a closed pharmacy. When I called, the operator told me to “take ibuprofen and wait ‘till Monday.”

By the time we got a doctor to realize the mistake, the closest 24-hour pharmacy was an hour away. On our first night home after a week in the hospital, my husband had to leave me with a toddler, a newborn and a painful wound.

A week out of the hospital, I discovered my C-section had reopened in three places. The doctors at the hospital pushed and prodded until I cried. They ignored my requests to not be touched so hard and not to use so much force. They bandaged it up after they were done and said it would be fine.

I wasn’t allowed to work out or lift heavy objects during this time. My toddler grew resentful that I couldn’t hold him. I spent my summer tied to the house, because we had to pack, blow dry and clean my wound every five or so hours.

I couldn’t swim, or even walk for more than 15 minutes. I sat on the side lines and watched my loved ones enjoy the spoils of summer.

I had to see a doctor monthly. They tried to close the incision by cauterizing the open parts. My hands shook when they came near my wound. I would leave the office feeling like a failure and scared to come back for another round of cauterizing.

One thing I heard over and over again from family and medical professionals alike, was, “well, at least you have a healthy baby.” It almost felt like my own health didn’t matter.

“The baby is the candy; the mom is the wrapper, and once the candy is out of the wrapper, the wrapper is cast aside,” Alison Stuebe, a doctor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina and advocate for maternal health, has said of the way mothers are treated post-partum in an interview with NPR.

Of course, I have endless gratitude for the fact that my child made it, but my wellbeing should have been considered equally important.

I was denied the ability to experience my trauma, I felt like society wanted me to put on the mask of “happy mother.”

When I discussed my experience with others, I heard myself take on the blame of what happened and apologize for complaining about something that was devastating to me.

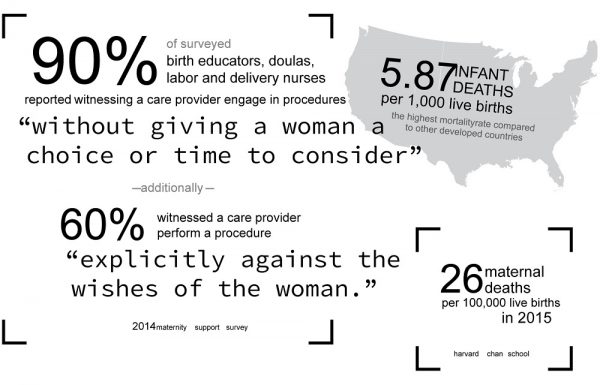

My story is just one out of the many cases where women have experienced some form of obstetric violence. Consent is too often breached. Far too many women end up feeling violated after their own birth experiences. In 2014, a California mother named Kimberly Turbin posted a video of her birth on YouTube, which included 12 episiotomy stitches given without her consent by a doctor. Turbin settled out of court in a landmark case against the doctor, who ultimately surrendered his medical license. Caroline Malatesta spoke out after a birthing center nurse held her child’s head inside of her to wait for a doctor to be present at birth. These are just two of examples of women who spoke out, and we have to ask ourselves, what about the women who don’t speak out, due to fear or other barriers?

Obstetric violence is real, and it’s a growing issue that is costing us lives of mothers and children. Doctors and patients need to learn how to communicate, and it’s on hospitals to have policies in place to make patient advocacy a priority. It’s time for the treatment of women in birthing situations to be discussed, safely, openly and truthfully. We must listen to women and start to value their health.